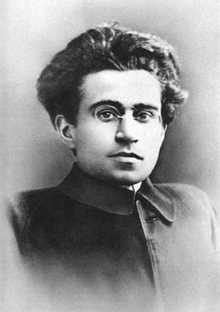

Gramsci: Revolutionary Activist

by Robin Wylie

One of the leading Marxist activists in the classical revolutionary socialist tradition is Antonio Gramsci, an Italian socialist militant who saw the revolutionary potential in Italy’s post-World War One strikes; who became the leader of the Italian Communist Party in the 1920s; and who, as a prisoner of Mussolini’s fascist regime, reflected on these experience to ask how a revolutionary socialist party can build ‘hegemony’ or moral authority to win over a majority of workers to transformational change.

The Italian Cauldron

Antonio Gramsci was born in 1891 in Sardinia. He came from a modest middle class background. His father was indicted for corruption as a government official and the family struggled to survive with young Antonio having to work at an early age – despite being hunchbacked and suffering from chronic respiratory problems.

In Sardinia the young Gramsci was attracted to a peasant protest movement that looked to independence as the solution to landlord exploitation. However, Gramsci’s older brother, who was doing his military service in Turin, opened up a more thoroughgoing alternative, sending him copies of Italy’s leading socialist newspaper, Avanti, the paper of the new Italian Socialist Party (PSI). This, and a scholarship to study at the University of Turin, drew Gramsci into socialist politics, to the struggles of urban wage workers and a political movement that looked to capture and transform the new Italian state.

Italy was a new state with enormous social tensions. Much of the country was agricultural and incapable of supporting its rural population. Millions of young Italians either left the rural South for the newly industrializing North, to cities like Turin or Milan, or emigrated abroad. Politically, despite the claim to be a constitutional monarchy, the majority could not vote until 1912.

In these difficult circumstances, Italian workers struggled to establish trade unions, often with the need to establish unofficial ‘ factory commissions’ to enforce collective agreements at the local level, and the PSI which either preached a verbal ultra-leftism, but adapted to the parliamentary practice of cross-class brokerage politics, or an abstentionist ultra-leftism that rejected any practical struggles that engaged such an exploitive economy and hypocritical democracy.

War and Workers’ Power: the Bienno Rosso

Despite being an ally of Germany, the Italian government declared neutrality in 1914 at the outset of World War One. In 1915, however, on secret promises by England and France of territorial gains, Italy joined the Western allies and opened a front against Austria.

World War One proved almost too much for the new state. Italy had neither the economic or political resilience to engage in prolonged total war. Militarily, the Austrians delivered a crippling blow at Caparetto in 1917 that the sent the Italian army in flight in the northeast. Economically, production of basic foodstuffs was dislocated and inflation took off, while workers’ pay stagnated. By 1917 there were bread riots by workers’ wives and the Turin Factory Commissions attempted to launch a general strike, which was isolated and crushed.

When the war ended, however, Italian urban workers and rural tenants were determined to force a better deal, better pay and conditions, and structural changes like the eight hour day and state subsidized rural co-operatives. For some, this also meant fundamental change through a revolutionary seizure of power. Thus began the bienno rosso, the two ‘red years’, of 1919 and 1920 when hundreds of thousands of new factory workers, in plants like Turin’s Fiat, occupied their workplaces – or where hundreds of thousands of rural workers occupied landed estates. Antonio Gramsci became the voice of this eruption.

Gramsci began his university studies in Turin innocuously enough in studying linguistics and philosophy in a complex milieu of Italian liberalism (Crocean idealism) and Marxism, especially in regards to the ideas of the Italian Marxist Labriola. But, given Gramsci’s youthful radical formation, he was soon drawn to the PSI, becoming a member in 1913, an educational speaker in 1915, and in 1916 a full time professional revolutionary – though more as a cultural journalist than party functionary.

Perhaps given his role as an imaginative thinker (and that most of the Turin PSI leadership had been arrested in 1917), Gramsci was one of the first PSI agitators to welcome and spread the ideas of Lenin and the Russian Revolution. On that basis, Gramsci saw the revolutionary potential of the self-organized Factory Commissions and the factory occupations. What the workers were doing defensively could be turned into offensive soviet power. The task was not just to get a better economic deal, nor about taking over the discredited war-promoting parliamentary state. The task was to build a new state of a new kind.

To publicize, reflect, and generalize this revolutionary potential, Gramsci founded a journal, L’Ordine Nuovo (the New Order) as the voice of the two red years. But he did not build independent party organization, even as a caucus within the PSI.

Party Builder: the United Front in extremis

The two red years did not lead to an Italian social revolution. The PSI and the trade union leadership, the CGI, refused to lead a worker-peasant seizure of power (going so far as to hold a referendum on the question while clearly signaling no one was prepared to lead). In fact, the PSI joined a ‘national’ government for a social contract to build employer-worker consensus, which was repudiated in months to end with the Italian army going into the factories in 1921.

Instead there was reaction – fascism; a new brutal form of capitalist political power built on the physical destruction of worker-peasant organization (squadrismo) led the ex-PSI leader Benito Mussolini – and a cynical deal by the old capitalist parties with the King to let Mussolini assume formal national power in 1922. This, to the surprise of all who believed in the immutability of parliamentary politics, led to a fascist dictatorship by 1926.

The Italian left was in disarray. The PSI continued to focus on parliament, yet also asked to join the Comintern, the Third International based in Moscow, thus continuing its old practice of ultra-left rhetoric and right wing parliamentary practice. The abstentionist left, led by Amadeo Bordiga, held a meeting in Venice to argue for an organizational break, the creation of an Italian Communist Party (PCI). Gramsci, as the leading Turin left representative, agreed but argued for a test of PSI rhetoric at its next convention. Bordiga, insisted on leaving without soiling one’s hands in debating the reformists. This purist approach even extended to condemning the arditti, or popular militias, who resisted fascist violence.

Under conditions of growing illegality, and fascist extra-legal violence, the new PCI embraced Bordiga’s ultra-left denunciation of engaging in any political compromise as a means to joint activity with other anti-fascists. In the Comintern, however, there was recognition that the revolutionary tide had turned. It was now necessary for revolutionary groups to do the difficult task of working with others for limited democratic purposes even in illegal circumstances – without compromising one’s political independence in ideas or organization. This strategy was called the United Front.

In the case of Italy, the Comintern recruited Gramsci as its representative (based in Vienna) and in 1924 managed to overturn Bordiga’s hold on the PCI executive to establish Gramsci as Party Secretary (who was elected a parliamentary member for the Venice region to give him parliamentary immunity). Building the party in such repressive circumstances, with much of the PCI leadership in covert opposition, was very difficult. But through his travels in the country to meet with what was an underground party and through his writings, Gramsci managed to organize a conference in Lyons, France that articulated a new United Front practice. This was embodied in a set of perspective documents know as the Lyons theses – supported by 90% of the delegates.

The Lyons theses set forward a detailed analysis of Italy’s economy (particularly the gap between the industrial North and rural South), the class struggle both rural and urban, Italy’s colonial project, and the new political phenomenon of fascism (a product of petit bourgeois dislocation and fanaticism). In particular, Gramsci argued the party would have to do two hard tasks: reorganize the party as an underground cellular organization and link up with anti-fascists in demanding a workers’ and peasants’ government.

The practical test of a United Front was not promising. In 1924 a PSI deputy, Matteoti, was assassinated and conservatives deserted the fascists. The majority in parliament set up an alternative Parliament, the ‘Aventine Secession’. But when Gramsci challenged the PSI and the Liberals to establish a Workers and Peasants Government, no action was taken. The PCI, bravely, went back into the Italian parliament to face the fascists alone in condemning their increasingly dictatorial rule. This added to the party’s moral authority in building organization, even if through a failed United Front initiative.

The Struggle for Hegemony

The Lyons theses were the highpoint of Gramsci’s organizational leadership. In November 1926 Mussolini ended parliamentary immunity and had Gramsci arrested. At Gramsci’s trial in 1927, the fascist judge declared ‘We must stop this brain for the next twenty years’. But the fascists did not stop Gramsci from thinking and communicating, despite the fact that he would remain in jail in poor conditions; with terrible health problems; and being politically opposed by PCI members (who returned to ultra-left sectarianism with Stalin’s condemnation of any co-operation with non-communists, the ‘Third Period’, a perspective Gramsci opposed); until his death in 1937.

What Gramsci did manage was to write a series of reflections, some complete, many partial, of some 2900 pages that were smuggled out of prison, though only to be published after 1945. These writings have become known as The Prison Notebooks. The Notebooks address a wide variety of questions from a long term Italian philosophical and historical context. They were also written in obscure language to escape the prison censor. The term The Modern Prince, for example, is a metaphor for the Communist Party.

One enduring question Gramsci addressed was the question of ‘hegemony’, a question raised by the Russian Communist Party in building the USSR in the 1920s. That is, how does the party build intellectual, moral, and practical authority to win over militants to the revolutionary project of constructing an alternative political-social order – which in western circumstances meant operating as a distinct minority at odds with the dominant ideas and political practices that most accepted. To put this task in Gramsci’s terms, how do revolutionaries win militants to ‘good sense’, as opposed to ‘common sense’?

If the question can be put simply, there is no simple answer in Gramsci’s elliptical and fragmentary prison writings. Certainly learning from the class struggle as framed by a serious engagement with history and theory, but being prepared to generalize and organize on that basis is a conclusion Gramsci drew as his experience of struggles in Turin, the two red years, and being leader of the PCI in the 1920s shows.

Some things are certain. The struggle for hegemony will be more than an academic contest of ideas as Grasmci’s actual life demonstrates. Nor should Gramsci’s struggle against ultra-leftism be confused as support for a social democratic practice.